Dave Hansford in Wellington, New Zealandfor National Geographic News

September 21, 2008

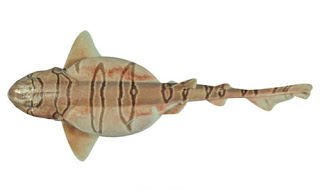

DNA evidence has helped identify 113 new sharks and rays—including a skinny saw shark, a swell shark that looks like it swallowed a Frisbee, and a river shark (see photos)—scientists announced Thursday.

Nearly half of the newly named sharks and other species are found only around Australia. The discoveries increase the continent's tally of known sharks and rays by a third. One of the new fish, the collared carpet shark, is so rare that the only known specimen was found in the belly of another shark.

September 21, 2008

DNA evidence has helped identify 113 new sharks and rays—including a skinny saw shark, a swell shark that looks like it swallowed a Frisbee, and a river shark (see photos)—scientists announced Thursday.

Nearly half of the newly named sharks and other species are found only around Australia. The discoveries increase the continent's tally of known sharks and rays by a third. One of the new fish, the collared carpet shark, is so rare that the only known specimen was found in the belly of another shark.

Some of the new species are already threatened with extinction, scientists say, and many of the sharks and rays have yet to be named.

(Also see: "New Sharks, Rays Discovered in Indonesia Fish Markets" [March 31, 2007].)

Defined by DNA

During the 18-month study, researchers used genetic techniques to help scientifically describe, for the first time, species already in museum collections in Australia, New Zealand, and Europe.

"We reviewed the entire shark and ray fauna," said fish taxonomist Peter Last, who led the project for Australia's Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO).

At first glance, some of the fish appear very similar, making it tough to tell different species apart. Some even share the same habitat. "Quite often, they will swim together," Last said.

Existing descriptions—many of them brief and lacking detail—weren't much help, Last said.

But by analyzing the species' DNA, the scientists were able to uncover invisible distinctions.

"In some cases, what was thought to be a single species of shark turned out to be something like five species," he said.

Among these previously "hidden" species is the newly described maugean skate, already listed as endangered by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature.

(Also see: "New Sharks, Rays Discovered in Indonesia Fish Markets" [March 31, 2007].)

Defined by DNA

During the 18-month study, researchers used genetic techniques to help scientifically describe, for the first time, species already in museum collections in Australia, New Zealand, and Europe.

"We reviewed the entire shark and ray fauna," said fish taxonomist Peter Last, who led the project for Australia's Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO).

At first glance, some of the fish appear very similar, making it tough to tell different species apart. Some even share the same habitat. "Quite often, they will swim together," Last said.

Existing descriptions—many of them brief and lacking detail—weren't much help, Last said.

But by analyzing the species' DNA, the scientists were able to uncover invisible distinctions.

"In some cases, what was thought to be a single species of shark turned out to be something like five species," he said.

Among these previously "hidden" species is the newly described maugean skate, already listed as endangered by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature.

Found in "three little estuaries" off the Australian island of Tasmania, the maugean skate is very similar to a species found on the other side of the world, off southern South America. Before breaking apart about 160 million years ago, Australia and South America were joined in the supercontinent Gondwana.

The similarity of the two skate species suggests that they were once a single species that plied Gondwana coastal waters, Last said. Since the breakup, the skates have hugged the coasts of Australia and South America, he said.

The similarity of the two skate species suggests that they were once a single species that plied Gondwana coastal waters, Last said. Since the breakup, the skates have hugged the coasts of Australia and South America, he said.

These animals have simply remained on the edges of the fragments of [the former Gondwana continental] plate all that time, without changing much"—though enough to now be considered separate species.

Lost Before Found?

Most of the new species—such as the southern dogfish, a gulper shark—live along Australia's continental shelf, a very narrow plateau that plunges steeply to the open deeps.

Living in this narrow ribbon of shallow water places the species in the path of trawlers, where the fish are vulnerable to overfishing.

Some species could go extinct before they are even fully described, Last said—a particularly consequence when top predators are involved.

"If you take the top predators out of the food chain, it can have serious implications for the rest of the ecosystem," he told National Geographic News.

"Part of the problem is … we've tended to try and manage groups of species rather than single species, and the biology of single species can be very different to groups," Last told the Australian Broadcasting Corporation yesterday.

Clive Roberts, curator of fish at the Museum of New Zealand, said, "A lot of these sharks are slow growing. They're long-lived and relatively slow reproducers, only dropping pups perhaps every second year.

"Because they are vulnerable to fishing, they become locally extinct fairly quickly," Roberts said. "That's been well documented around Australian waters."

More to Come

New large marine species will continue to turn up, he added.

"We're still describing new species from 10 or 13 feet [3 or 4 metres] depth, so it's no surprise that there are heaps of undescribed stuff further down.

"We need to know what we've got, and where it is," Roberts said. "We need to know what species it is and manage it, conserve it, or exploit it in a responsible way."

Lost Before Found?

Most of the new species—such as the southern dogfish, a gulper shark—live along Australia's continental shelf, a very narrow plateau that plunges steeply to the open deeps.

Living in this narrow ribbon of shallow water places the species in the path of trawlers, where the fish are vulnerable to overfishing.

Some species could go extinct before they are even fully described, Last said—a particularly consequence when top predators are involved.

"If you take the top predators out of the food chain, it can have serious implications for the rest of the ecosystem," he told National Geographic News.

"Part of the problem is … we've tended to try and manage groups of species rather than single species, and the biology of single species can be very different to groups," Last told the Australian Broadcasting Corporation yesterday.

Clive Roberts, curator of fish at the Museum of New Zealand, said, "A lot of these sharks are slow growing. They're long-lived and relatively slow reproducers, only dropping pups perhaps every second year.

"Because they are vulnerable to fishing, they become locally extinct fairly quickly," Roberts said. "That's been well documented around Australian waters."

More to Come

New large marine species will continue to turn up, he added.

"We're still describing new species from 10 or 13 feet [3 or 4 metres] depth, so it's no surprise that there are heaps of undescribed stuff further down.

"We need to know what we've got, and where it is," Roberts said. "We need to know what species it is and manage it, conserve it, or exploit it in a responsible way."

No comments:

Post a Comment